More often than not, a film that projects liberal sensibilities and blatantly pushes messages about the importance of togetherness, tolerance, building bridges and all those other wonderful ideals that cause ageing hippies to go misty-eyed, leaves you with the feeling that what you’ve just watched has been preaching to the converted. Ken Loach’s work comes to mind in this regard. His movies invariably present a socially-minded agenda — frequently to terrific effect — but their style causes them to be publicised to, and seen by, the sorts of people who probably subscribe to his philosophies already. This is a huge generalisation of course, but I’m sure you get the point. Having seen many such ‘echo chamber’ films, I’ve frequently wondered what a movie-maker would have to do in order to preach successfully to the unconverted.

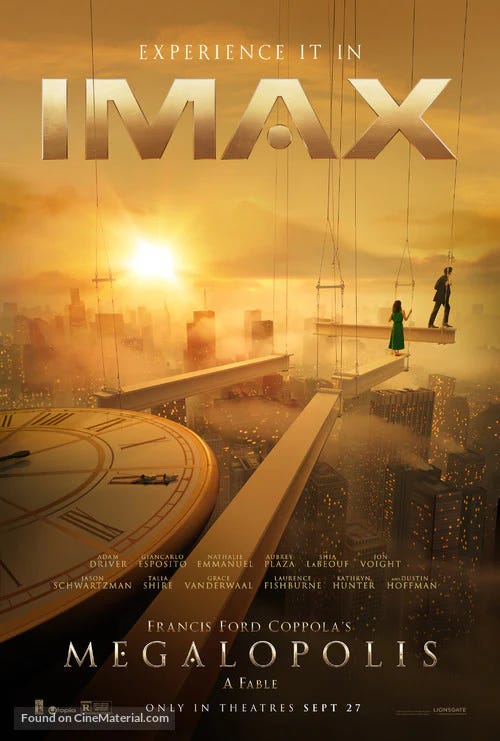

One answer might be to create something like Megalopolis. Francis Ford Coppola’s sprawling, rambunctious, bombastic extravaganza finally comes to us on a tornado of hyperbolic marketing and what are largely scathing reviews. It’s a great big hollow nothing, is what most critics seem to be saying: an example of zero style over even less substance. That may well be true, but I wonder if attempting to view the movie in what may be called traditional critical terms was always bound to frame it as a failure, because if Megalopolis works on any level, then I’d suggest it’s only if seen as a cri de coeur from an elderly man who appears absolutely desperate to sort out the ills he sees around him and just get people to stop being horrible to each other. And he doesn’t want his plea to be heard by those who don’t particularly need to hear it, but by everyone.

From the very start, the film makes its unsubtle ambitions quite clear. Not only does it begin with a portentous caption: it also employs the services of a narrator (the suitably booming-voiced Laurence Fishburne) to read the caption to the audience. The very definition of spelling things out, the technique sets the tone for everything else that is to come. And what is that, precisely? Well, one of the criticisms aimed at the movie is that its screenplay (also by Coppola) is incomprehensible, but that isn’t quite true. The plot is fairly easy to grasp; indeed, if anything, it’s overly simplistic.

In the city of New Rome - suffering from poverty, division and a rather old-fashioned take on sin and debauchery - Cesar Catilina, played by an appropriately otherworldly Adam Driver, is convinced he’s found the solution to society’s problems. If only he could be permitted to build his dream city of Megalopolis, using an ingenious material he’s invented called ‘megalon’, then all barriers between people would collapse and everyone would enjoy the proverbial ‘happily ever after’. But of course, greed, corruption and jealousy stand in his way, in the form of, amongst others, the father of the woman he’s fallen in love with (there’s often a shade of Romeo & Juliet to this tale), a treacherous media personality (the hilariously named Wow Platinum) who’ll stop at nothing to reach the summit of this pseudo-Roman empire, and an envious cousin with a particularly nasty grudge against him.

In other words: a pretty familiar story. But it’s the way it’s been presented that makes Megalopolis one of the most unusual pieces of work we’re ever likely to witness at the cinema. Nearly every single frame is filled with some form of visual or auditory excess. When Catilina is seen driving through the city, a gigantic statue of Justice comes to life and literally holds its head in despair. When everything becomes a bit too much for him and he needs to give himself a moment to think, well, Catilina snaps his fingers and stops time. And in one sequence, when a bandage around his face is unfurled and briefly looks like a Gandhi-esque turban, his image is split into hundreds of identical reflections, accompanied by a musical motif suggesting he’s turned into some kind of Hindu god or guru. It is all relentless, over-the-top and preposterous — not unlike a music video extended across 138 minutes — and yet somehow it manages to remain compelling.

Key to this magnetism are the special effects. In Bram Stoker’s Dracula (a work of monkish restraint by comparison), Coppola indulged his love of old-school visual wizardry: many of the effects had an unpolished feel, paradoxically causing them to come across as more real and more convincingly part of the action on screen. The director follows a similar approach here, never permitting the visuals to feel too slick or artificially generated. Witness a scene where a hand emerges from a cloud and steals the moon: with its echoes of Melies, it strikes a more powerful chord than a more seamless effect might have been able to.

The design is intriguing too. Yes, Catilina’s vision of Megalopolis features organic-looking, biologically intertwined structures of a type we’ve seen in other examples of sci-fi. But the endless repetition of images of interconnectedness — at one point, twin foetuses inside a woman’s womb appear to split up into several other bodies which then meld into the fabric of a sea bed — does carry an undeniable force. Coppola wants us to know that we’re all inhabitants of one small planet, and he will stop at nothing to make his point abundantly clear.

If all this makes it sound as though I’m giving the film a thumbs up, I should point out that I remain bemused by it. I thought it was bizarre, cumbersome and astonishingly superficial — in the sense that it places everything it wants to say clearly and overtly on its surface — but I found it impossible to dismiss. I’m also not sure, to return to the point I was making above, that it successfully preaches to anyone, even though a part of me wants to applaud its attempt to push a socially-minded agenda without the slightest hint of a Loach-ian, social realist style.

Maybe the most helpful key to understanding it lies in its full title — Megalopolis: A Fable. It may not be suitable for children, but otherwise this is a story that relies on broad character types, simple plot developments, basic narrative hooks (love, betrayal, power), grand set-pieces and clear-cut (perhaps even naive) black-and-white morality. And it does so unashamedly, which may well be its saving grace. I expect it’ll perform miserably at the box office right now. But I wouldn’t be at all surprised if, in years to come, it takes on the status of a flawed, perplexing and yet utterly unique cult classic.

Dariush

Really odd... I don't exactly look forward to seeing this one, but there's no way I will let it disappear from cinemas before having seen it on the biggest screen I can find. The last time I went out to catch a *new* Coppola was in 1992 (Dracula on a first date, I remember the whole thing vividly); never thought I'd get to do it again.

How funny, I watched this last night with my begrudging friend, another friend and her skeptical husband (who claimed it was the worst movie he's seen in theaters in over a decade). As a parody I think it was quite effective, though I think it was a bit more true-intentioned than that. Your "fable" theory does make more sense, actually. I was fully entertained (unlike in Dracula which I think WAS a parody and was not successful), though I cannot in good conscience call it a good movie. Ultimately Megalopolis felt like The Fountainhead directed by Baz Luhrmann, and most of the negative things I've read about it are wholely accurate. I gave it five stars on letterboxd.

I should "post script" and say I've only seen a handful of Coppola's movies, and not the ones you'd guess. So take this with a grain of salt.